Amortized Analysis

Amortized analysis analyzes the costs associated with a data structure that averages the worst operations out over time.

A data structure has one particularly costly operation, but it doesn’t get performed very often. That data structure shouldn’t be labeled costly just because that one operation, which is seldom performed, is costly. So, amortized analysis is used to average out the costly operations in the worst case. The worst-case scenario for a data structure is the absolute worst ordering of operations from a cost perspective. Once that ordering is found, then the operations can be averaged.

=> Refers to determining the time-averaged running time for a sequence operation, not an individual. It is different from average case analysis because we don’t assume that the data is arranged in an average fashion, not very bad, as we do for average case analysis for quick-sort. It applies to the method that consists of the sequence of operations, where a vast majority of operations are cheap but some of the operations are expensive.

The amortized analysis gives us the average performance of a series of operations in the worst case. It is useful when an operation or a set of operations occur successively, but only very a few of them have a bad complexity.

Three main types of amortized analysis - Aggregate analysis : Calculate the total cost of n operations first - Accounting method : save coins to a “virtual bank” when an operation is “cheap”, and we use the saved coins to pay for an “expansive” operation. - Potential method

Increment in a binary counter

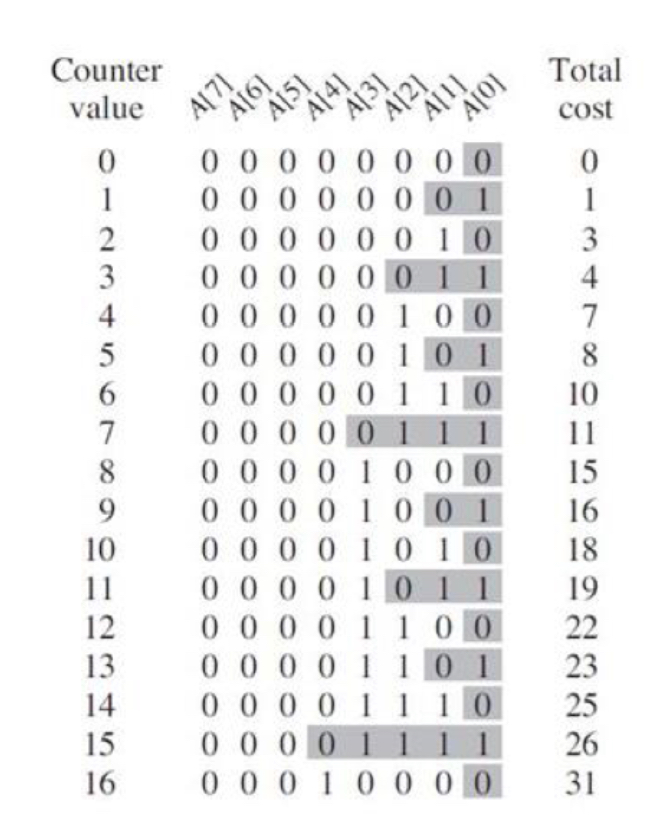

Given a (k-bit) binary counter A, we can see the time complexity of an Increment(A) is the number of flips to increase the counter value by 1. For example, in this binary counter, the cost to increment from 7 to 8 is 4, since we need to flip 4 digits. In general, it is easy to see that Increment(A) has worst-case time complexity k, since we might need to flip all digits in one incrementing.

The amortized cost of Increment(A)

Aggregate analysis

On the right-hand side of the counter in the above image, we can see that after 16 calls, the total cost of Increment(A) is 31, we can guess that the amortized cost of Increment(A) is \(\frac{31}{16} \approx 2\), which is a constant and independent from k

A common example is a modified stack.

Observation

The least significant bit flips in every increment, the second least significant bit flips in every two increments, and the third insignificant bit flips in every four increments… If there are m Increment(A) operations, the total running time is : \(m + \frac {m}{2} + \frac {m}{4} + \cdots = 2m\). Thus, the amortized cost of Increment(A) is \(\frac {2m}{m} = 2\).

Accounting method

Accounting method is aptly named because it borrows ideas and terms from accounting.

Each operation is assigned a charge, called the amortized cost. Some operations can be charged more or less than they actually cost. If an operation’s amortized cost exceeds its actual cost, we assign the difference, called a credit, to specific objects in the data structure. Credit can be used later to help pay for other operations whose amortized cost is less than their actual cost. Credit can never be negative in any sequence of operations. The amortized cost of an operation is split between an operation’s actual cost and credit that is either deposited or used up. Each operation can have a different amortized cost, unlike aggregate analysis. Choosing the amortized cost for each operation is important, but the costs must always be the same for a given operation no matter what the sequence of operations, just like for any method of amortized analysis.

Assume that each flip is worth 1 coin (1 operation), but we pay one extra coin (and save the coin on that digit) when flipping a digit from 0 to 1. We use that saved coin to flip that digit from 1 back to 0 later.

Observation

In each Increment(A) operation, we flip exactly one digit from 0 to 1. Whenever we need to flip a digit from 0 at the \(q^{th}\) insignificant digit to 1, we need to flip all the q - 1 insignificant digits from 1 to 0.

Thus, an Increment(A) operation that the \(q^{th}\) insignificant digit from 0 to 1 has amortized cost: \(2 + 0 \times (q - 1) = 2\).

Potential method

The potential method is similar to the accounting method. However, instead of thinking about the analysis in terms of cost and credit, the potential method thinks of work already done as potential energy that can pay for later operations. This is similar to how rolling a rock up a hill creates potential energy that then can bring it back down the hill with no effort. Unlike the accounting method, however, potential energy is associated with the data structure as a whole, not with individual operations.

A potential function \(\Phi\) is defined on a data structure or a system, it describes the “potential energy” stored (or “money” saved) in a system or a data structure. For the same system, the potential function \(\Phi\) can be defined in many ways, but we require that \(\Phi\) needs to be non-negative after each operation. It’s like a debit card, sometimes you need to use your savings, but you are not allowed to have a negative amount of money in the account.

For \(i = 1, 2, \cdots\) let \(c_i\) be the actual cost of the \(i^{th}\) operation in a series, let \(\hat{c_i}\) be the amortized cost of the \(i^{th}\) operation, let \(D_i\) be the system after the \(i^{th}\) operation and \(\Phi(D_i)\) be the potential in the system after the \(i^{th}\) operation,

\[\hat{c_i} = c_i + \Phi(D_i) - \Phi(D_{i-1}) = c_i + \Delta(\Phi(D_i))\]=> The amortized cost of the \(i^{th}\) operation equals to the actual cost of theat operation plus the change that operation makes in the potential.

It is not always easy to find a useful potential function, but in general we want the potential to increase a little after a “cheap” operation and the potential drops a lot after an “expansive” operation.

For binary counter, can define \(\Phi\) as “number of 1’s on the binary counter”, and use \(A_i\) to represent the binary counter after the \(i^{th}\) Increment(A) operation. Increment(A) operation which flips the \(q^{th}\) insignificant digit from 0 to 1 has amortized cost:

\[\hat{c_i} = c_i + \Phi(A_i) - \Phi(A_{i-1}) = c_i + \Delta(\Phi(A_i))\] \[= q + (1 - (q - 1))\] \[= 2\]Using different potential functions on the same system will give you different amortized costs. If the function didn’t give you an amortized cost as you expected, it means this potential function is not useful for this system, and it doesn’t mean all other potential functions cannot give you the expected amortized cost.

Prove

A typical way to do this is to define \(\Phi(D_0) = 0\) and show that \(\Phi(D_i) \ge 0\). => The \(i^{th}\) operation will have a potential difference of \(\Phi(D_i) - \Phi(D_{i-1})\). If this value is positive, then the amortized cost $a_i$ is an overcharge for this operation, and the potential energy of the data structure will increase. If it is negative, it is an undercharge, and the potential energy of the data structure will decrease. At the binary counter. The potential function chosen will simply be the number of operations on the binary counter. Therefore, before the sequence of operations begins, \(\Phi(D_0) = 0\) because there are no operations in the binary counter. For all future operations, it’s clear that \(\Phi(D_i) \ge 0\) because there cannot be a negative number of operations in the binary counter. Calculating the potential difference for an Increment(A) operation, we find that \(\Phi(D_i) - \Phi(D_{i-1}) = (size + 1) - size = 1\) So, the amortized cost of the Increment(A) is \(a_i = c_i + \Phi(D_i) - \Phi(D_{i-1}) = 1 + 1 = 2\) All of these operations have an amortized cost of \(O(1)\), so any sequence of operations of length n will take O(n) time. Since it was proven that \(\Phi(D_i) \ge \Phi(D_0)\) for all \(i\), this is a true upper bound. The worst case of \(n\) operations are therefore \(O(n)\).

Example

We’ve seen that A[1] is flipped \(\frac{n}{2}\) times and that A[2] is flipped \(\frac{n}{4}\) times. For an A of length k, how many bits are flipped for n increment operations? What does this mean for aggregate analysis?

-> For each A[i] where \(i\) is \({0, 1, \cdots, k-1}\), bit \(i\) is flipped \(\frac{n}{2^i}\). The summation is then \(\Sigma_{i = 0}^{k-1} {\frac{n}{2^i}} < n\Sigma_{i=0}^{\infty} {\frac{1}{2^i}} = 2n\). So, there are 2n flips and this takes \(O(n)\) times. Using aggregate analysis \(\frac{T(n)}{n} = \frac{O(n)}{n} = O(1)\).

Suppose we wish not only to increment value in a 𝑘-digit binary counter 𝐴, but also to reset the value in 𝐴 to 0. Counting the cost of each flip as 1, can you implement Increment(𝐴) and Reset(𝐴) such that any sequence of 𝑚 Increment(𝐴) and Reset(𝐴) operations cost 𝑂(𝑚)? In other words, each operation in the sequence has amortized cost 𝑂(1), which is a constant and independent from 𝑘. If you can, show how; if you think it is impossible, show why.

=> Yes, it is possible. It uses a binary representation of A as an array of k bits. Increment(A) operation is performed as starting from the least significant bit, flip the first 0 bit encountered to 1 and if 1 bit is flipped to 0, repeat the previous step for the next bit until 0 bit is flipped to 1 or the most significant bit is reached. Each bit flip in an Increment(A) operation costs 1. However, the number of bits that need to be flipped is at most k, which is constant. Thus, the amortized cost of an Increment(A) operation is O(1). The Reset(A) operation is performed by setting all bits to 0. It costs k flips, which is also a constant. Therefore, the amortized cost of a Reset(A) operation is O(1). The Increment(A) operation flips a maximum of k bits and the Reset(A) operation flips k bits. Therefore, any sequence of m operations a A has an O(m) cost in total, which means that the amortized cost of each operation in the sequence is O(1).

Reference

- CS 430, Introduction to Algorithm, prof. Wang, Xiaolang, Spring 2023, Illinois Institute of Technology

- Amortized analysis. Brilliant Math & Science Wiki. (n.d.). brilliant.org/wiki/amortized-analysis

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: